Walerian Borowczyk, 1981

Starring: Udo Kier, Marina Pierro, Patrick Magee, Howard Vernon, Clement Harari

Dr. Henry Jekyll and his beautiful fiancee, Miss Fanny Osbourne, hold a party in his home to celebrate their impending union. Just before the party begins, a raped and murdered girl is found outside the house, which foreshadows things to come. The stuffy guests, lulled into complacency with food, drink, and discussions of their own importance, soon find themselves under siege by an alien-looking figure — Mr. Hyde — who rapes, tortures, and murders his way through the house. It seems that Jekyll has discovered a chemical formula that unleashes the beast within and Jekyll transforms back and forth into Hyde, while searching the house for objects of his desire — particularly the lustful Miss Osbourne.

Director Walerian Borowczyk’s only film that could truly fit into the horror genre is this masterpiece, a bizarre, phantasmagorical delight. With a score from avant-garde composer Bernard Parmegiani and some impressionistic cinematography from Borowczyk’s regular collaborator, Noël Véry, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osbourne is both the culmination of Borowczyk’s themes and his last great work. This French-West German coproduction is based on The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, but is one of the few filmic adaptations of this famous horror tale to recreate Robert Louis Stevenson’s many moments of violence and sexual terror.

Though the producers gave the film the title Docteur Jekyll et les femmes (Dr. Jekyll and the women), there is only really one femme of importance here — Fanny Osbourne — which is reflected in the title Borowczyk desired, Le cas étrange de Dr.Jekyll et Miss Osbourne. Like his earlier films, Borowczyk focuses on female sexuality, particularly in it escaping the bounds of restrictive bourgeois society. Here Fanny as shown to be aroused by Jekyll — their passionate kissing in his laboratory suggests a pre-existing sexual relationship — but this smooth, charming scientist is played with aplomb by the handsome Udo Kier (one of the few actors I know of to play Dracula, Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll, and Jack the Ripper), so I can’t really blame her. Marina Pierro, who stars as Fanny, was one of Borowczyk’s two muses and the director often captured some fantastic representations of unrestrained sexuality when she was on screen.

Fanny and some of the film’s other female characters are perhaps inexplicably aroused by the alien-like Hyde. With a shaved head, dilated pupils, and an enormous (almost comical) penis, he’s a terrifying figure and a welcome departure from Hollywood’s traditional depictions of an ape-like, devolved Hyde. Here he suggests an unsettling sort of evolution and the film’s gloriously Sadeian elements imply that sexual freedom is inherently violent, chaotic, and asocial. Though I think Kier could have commanded the role (just look at him in Flesh for Frankenstein), Gérard Zalcberg (Jess Franco’s Faceless) is brilliant and, like the beast in Borowczyk’s La bête, is a convincing combination of monstrosity and all-consuming sexuality.

Compared to all of Borowczyk’s other films, this is the most closely related to the little seen Lulu, which features Udo Kier as Jack the Ripper in the film’s final scene and is another adaptation of a Victorian-era text. Like Dr. Jekyll, Lulu is concerned with a morally uninhibited character (the titular Lulu) violently rupturing the constraints of Victorian society. Like Lulu’s lovers, all of whom are driven to death soon after having sex with her, several of Hyde’s victims are willing participants in his rituals of sex and slaughter. But what that film lacks in sex and violence, Dr. Jekyll delivers in spades, challenging the viewer at every turn.

But this is more than a horror film. Like Pasolini’s Teorema or Buñuel’s Exterminating Angel, this is also a social farce. Borowczyk mocked Victorian sensibilities repeatedly throughout his career, but this theme reached its height here. The characters include uptight family members, a clergyman, and a scientist, and the majority of the film is set inside a small Victorian mansion that is at once labyrinthine and claustrophobic. Mr. Hyde’s rampage reveals scenes full of mirrors, oddly angled doorways, and murky, candlelit chambers.

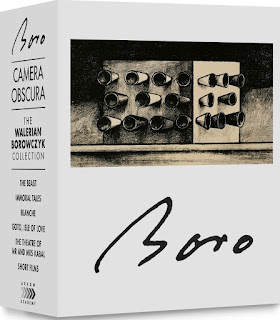

Obviously The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osbourne will alienate a lot of viewers — including even the staunchest gore fans — but it comes with the highest possible recommendation. And luckily Arrow Video has given it a mind-blowing Blu-ray release, which came out earlier this year. While their box set dedicated to Borowczyk’s earlier career, Camera Obscura, is a thing of collector dreams and fantasies, Dr. Jekyll is actually able to give it a run for its money. In addition to an audio commentary featuring everyone from Borowczyk himself (from archival material) to Noel Very, other crew members, and Daniel Bird, the disc is packed with interviews from stars Udo Keir and Marina Pierro, among others. There are a handful of fascinating featurettes of varying length, short films, and more. If Camera Obscura was the release of 2014, this surely takes the cake for 2015.

And really, the world could do with a few more films that involve a manic running around with a bow and arrow.