Born Jean-Pierre Grumbach, the great director took his stage name, Melville, from the time he spent serving the French Resistance during WWII. Melville was his code name and reflects his love of American culture. The fact that he continued using the name after the war also reflects the importance of his Resistance experience on his life. His family were Alsatian Jews and he was forced to go into hiding during the war. Though his films Le silence de la mer and Léon Morin, prêtre were both set during the war, only his classic, L’armée des ombres, gives an accurate glimpse of his WWII experiences. After the war, when the French government turned down his application to become a director, he took matters into his own hands and was one of the first French filmmakers to create his own studio.

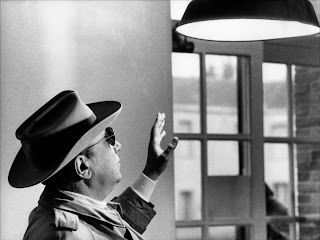

Between the late ‘40s and early ‘70s, Melville made 13 feature films. Most of these are crime films with a focus on police, gangsters, and capers, though a handful of his early films are meditative dramas. He was heavily influenced by the American noir films of the late ‘40s and early ‘50s. In turn, he deeply influenced if not outright began the French New Wave/nouvelle vague, as well as later crime and heist films. He was one of the first French directors to break out of the studio and use real locations, as well as an almost magical realist sense of space, lighting, and geography. Notably, he helped popularize the stylish criminal with most of his characters - as well as himself - regularly donning sunglasses, a trench coat, and Stetson hat.

Melville was truly an auteur, not only directing his films, but writing most of them, becoming involved in set and costume design, cinematography, etc. He regularly worked with the same actors and his most famous stars include Jean-Paul Belmondo, Lino Ventura, and Alain Delon. Much of his incredible lighting and cinematography is due to Henry Decaë, who he worked with throughout his career. Melville was not only a director and appeared in some notable films as an actor, such as Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (1949), Eric Rohmer’s Le signe du lion (1959), Jean-Luc Godard’s A bout de souffle (1960), Louis Malle’s Zazie dans le métro (1960), and Claude Chabrol’s Landru (1962), among others.

On to his films.

Melville’s first feature length film took me completely by surprise. Jess Franco regular Howard Vernon stars as a charming Nazi officer who boards with an elderly French man (Jean-Marie Robain) and his young niece (Nicole Stéphane) in their country home. They are not pleased to have him and revolt by maintaining a stubborn silence, despite his daily monologues about his love of France and French culture. He feels affection for the small family and firmly believes that the war will unite France and Germany.

This meditative, bittersweet film kicked off Melville’s main theme of characters who are drawn together, but remain fundamentally at odds. He would also go on to make a number of films about WWII and it is surprising to see such a sympathetic, charismatic Nazi character so soon after the war. The cinematography is some of his most beautiful and pastoral and the film revolves around daily domestic activities, another theme Melville would regularly explore.

Based on Jean Cocteau’s novel of the same name, Melville’s second film concerns the unhealthy relationship between brother and sister Paul (Cocteau’s paramour Edouard Dermithe) and Elisabeth (Nicole Stéphane). A series of unfortunate events - an accident at school, the death of their mother, the death of Elisabeth’s wealthy new husband - brings them closer together and removes all obstacles from their increasingly internalized lives.

Though made up of selfish, frustrating, and unlikable characters, Les enfants terribles is one of Melville’s most psychologically complex films and Bernardo Bertolucci’s celebrated film The Dreamers steals unmercifully from it. Stéphane, returning from Le silence de la mer, may not have been Melville’s most beautiful lead actress, but she was definitely his most compelling and carries this film with a steely gaze and varied performance. Cocteau, a director in his own right and screenwriter here, commissioned Melville to adapt his very popular novel. Their working relationship was somewhat troubled and the film suffers from Cocteau’s insistence on casting Dermithe, who simply cannot compete with Stéphane. But the finished film is clearly Melville’s work, further developing themes from Le silence de la mer and introducing new visual concepts - such as black and white tiled floors - that would appear repeatedly in his later work.

This melodrama about the fraught relationship between a con man and an ex-nun is perhaps my least favorite Melville film, but still has plenty to offer fans of early romantic drama. French pop idol Juliette Gréco stars as Thérèse, an aspiring nun who leaves the convent when her parents die in a car crash and she must care for her teenage sister, Irène (Yvonne Sanson). After a chance encounter, the innocent and lovely Irène develops a crush on Max (Philippe Lemaire), a boxer, mechanic, and con man. They have a second chance meeting where Max rapes Irène and she tries to kill herself out of shame, but survives. Thérèse tracks down Max and blackmails him into marrying her sister, who loves him despite the rape. Unfortunately for all involved, Thérèse and Max develop a poisonous love-hate relationship that will effect the happiness of all.

Too melodramatic for my taste, Quand tu liras cette lettre is an interesting film because it contains another of Melville’s most powerful female characters, Gréco’s Thérèse. Though she intended to take religious vows at the start of the film, Thérèse is anything but sweetness, light, or naive; she is cold, independent, and ruthless. The frustrated romantic struggle between two opposing characters introduced in Melville’s first two films continues here and is further complicated by a moral debate.

Quand tu liras cette lettre is not currently available on region 1 DVD.

Melville’s first film to be openly influenced by the American noir genre, Bob le flambeur relates the tale of an aging gambler, Bob (Roger Duchesne). He has mostly given up on the criminal life, though he maintains a passionate gambling habit and still interacts with the Parisian underworld. Tired of always being broke, he and a few colleagues decide to rob the Deauville casino, but things go wrong and the police get wind of their plans. On the night of the robbery, Bob gets to the casino early and begins to gamble...

Influential to both the French nouvelle vague and contemporary gangster films, Bob le flambeur presents sympathetic underworld figures, friendships between crooks and cops, and a sense of whimsy that would not appear in any of Melville’s other films. The particular sense of morality exhibited by Bob would reappear in nearly all of Melville’s gangster films, though Bob le flambeur is the most lighthearted of these. Elements of the heist planning scenes would certainly resurface in future crime movies, such as The Italian Job (1969).

Though this is one of Melville’s least popular films, it’s among my favorite, probably because of the pronounced involvement of Melville himself. In addition to directing, he stars as Moreau, a dogged reporter on the trail of a missing United Nations delegate from France. Along with an alcoholic photographer (Pierre Grasset), Moreau spends one long night following the only available leads - several pictures of women who may be the delegate’s girlfriends - to track down the missing man.

His first film shot in America, Deux hommes dans Manhattan may not be the most complex mystery, but it perfectly captures Melville’s love for cities, his passion for America, and his interest in early American noir and gangster films. Melville’s on screen charisma was a surprise and remains the most delightful aspect of this odd film. Lacking some of Melville’s more pronounced themes, it prefigures Léon Morin, prêtre in the sense that it is essentially a lengthy moral argument disguised as a detective story. This straightforward tale of the reporter, photographer, and missing politician is really an unfolding debate about private versus public life, individual and family identity, and an examination of privacy and moral responsibility.

Melville’s most subtle and enjoyable exploration of morals and identity is this unusual tale of an atheist communist and a country priest debating their individual belief systems in the Nazi occupied French countryside. Barny, played by the lovely Emmanuelle Riva (Hiroshima, mon amour) finds herself attracted to the young, handsome Father Léon (Jean-Paul Belmondo, in his first role with Meville). Though she initially resists, Léon wins her over and their weekly debates about the folly of religion turn Barny into a devout Christian.

In the most female-centric of all Melville’s films, Léon Morin is one of the sole male voices - particularly attractive young male voices - in a small French Mediterranean village and naturally all the town’s available women are hot on his trail. Though Melville could have easily made this into a tale of lurid, forbidden romance, as with Le silence de la mer, Les enfants terribles, and Quand tu liras cette lettre, this is really a film about longing, repressed desire, and the endless search for identity and personal freedom. Though this is perhaps the least action packed of all Belmondo’s films, he and Riva are a compelling pair and make this quiet, personal film an undeniable success.

Jean-Paul Belmondo returned to star in this dark, twisting tale of heists, gangsters, murder, theft, and betrayal. A thief named Maurice (Serge Reggiani) kills his acquaintance Gilbert (René Lèfevre) and steals a number of jewels and cash Gilbert was hiding after a recent robbery. Maurice plans a new heist with his friend, Silien (Belmondo), but is determined to get revenge after it seems Silien double crossed him.

Le doulos is the first of several dark-toned gangster films Melville made after the light-hearted Bob le flambeur. Boasting some truly incredible cinematography, Le doulos is primarily concerned with the world of male gangsters - female characters in his next six films would be sparse - and focuses on the meaning of friendship and loyalty. This is also the first of several Melville crime films where any notion of black and white morality is quickly abolished. The script subtly, gradually unfolds the parallel plots of Maurice and Silien, constantly reforming what we think we know of the two characters, their motivations, and what they are capable of. This is also the first in a long series of films where nearly all the major characters would die at the end of the film.

Belmondo returns again for this strange road trip film about a downtrodden young boxer who takes an impromptu job as secretary for a corrupt banker (Charles Vanel) on the run from the French police. After flying to New York, they try to collect all of Ferchaux’s savings in the U.S., but meet with some difficulties and are forced to hide out in swampy Louisiana. There the banker falls ill and tensions between he and the young secretary are at their most volatile.

Melville’s first color feature and second film shot in the U.S., L’aîné des Ferchaux is also concerned with male friendship, loyalty, and identity. Though the banker Ferchaux and his secretary come from opposite walks of life, they are inherently similar. Greedy, corruptible, and selfish, Ferchaux and Maudet are dependent on one another and their relationship becomes increasingly bitter. While the two lead actors give strong performances, as always (Vanel was known for The Wages of Fear, To Catch a Thief, and many more), and there are some captivating set pieces, L’aîné des Ferchaux exposes some of the pitfalls of the road trip film, such as plodding travel scenes and the constant interruption of the film’s building tension.

In my opinion, Melville’s first masterpiece is this carefully paced, gloriously shot film about Gu (Lino Ventura), an aged gangster who breaks out of prison and escapes to Paris, into the arms of his patient, faithful mistress (Christine Fabréga). She devises an elaborate plan to help him escape to the countryside and out from under the noses of the French police, where the two of them will live out the remainder of their lives. But Gu can't resist taking part in one last heist, though things to do not go as he hoped...

Despite some great male leads in Melville’s other films, the gruff, Italian Lino Ventura is my absolute favorite. He is perfect as Gu, a character who elegantly sums up Melville’s ideal protagonist. Gu may be a denizen of the criminal underworld and can clearly not resist the adrenaline rush of a final heist, but his oddly moralistic personality is a blend of fiercely loyalty and doggedly independence, coldly rationality and warm generosity. Le deuxième souffle is also noteworthy for two incredible sequences - the first during a lengthy heist scene and the second where opposing character case a room that will be a future meeting place - that have undeniably influenced future crime films.

Melville’s second masterpiece and perhaps his most popular film is this bleak, stylish gangster flick starring Alain Delon as Jef Costello, a successful assassin. His luck changes when he is hired to murder a nightclub owner and is almost caught by the police. He’s temporarily saved by an alibi from his prostitute girlfriend (Delon’s then wife Nathalie Delon) and a false statement from the only witness, a nightclub singer (Cathy Rosier). Costello must figure out who contracted the hit before he is the next victim or the police close in on him.

In many ways, Le samouraï is the culmination of all of Melville’s gangster films and blends a well-written, simple script with a great leading performance, excellent overall casting, dazzling visuals, and a carefully constructed soundscape. Though Melville would play with dialogue, silence, and soundtrack in his other films, here sound is at its most precise, including a lengthy opening sequence with no dialogue. Delon, with his handsome face and icy, assured stare, regularly asserts that he does not need dialogue to play a convincing, sympathetic Costello. Melville enhances Delon’s largely non-verbal performance with close up shots of Costello’s pet canary, either peacefully resting or anxiously flapping its wings and rustling its feathers in a small cage. This is the ideal place to begin for Melville novices.

Melville’s most perfect, accomplished film is this dark, nihilistic tale about the French Resistance, based on Melville’s own experiences with the Resistance. Lino Ventura stars as Philippe Gerbier, commander of a branch of the Resistance. L’armée des ombres catalogues his various adventurous, including his arrest, time spent in a prisoner of war camp, escape, punishment of an agent of the Resistance who betrayed him, and traveling to London with the secret head of the Resistance (Paul Meurisse). When Gerbier’s second in command is imprisoned and tortured, he and his accomplices must organize a dangerous rescue mission from which they may not return.

This biographical film was not popular upon its theatrical release, but has since become considered a classic. It is my favorite of all Melville’s films and provides a bleak look at life during the French Resistance. Melville incorporated many of the elements from his previous crime films - incredible cinematography, powerful performances (Simone Signoret and Jean-Pierre Cassel are wonderful in side roles), themes of loyalty and underground societies - though the heist scenes are replaced with rescue missions and anti-Nazi actions. This deeply personal film expresses both the necessity and futility of the Resistance movement, outlining its minor successes and pervasive frailties. Lino Ventura gives the best performance of his career and one of the finest in ‘60s French cinema. While L’armée des ombres comes with the highest possible recommendation, it is a devastating film and left me unable to watch anything else for a few days afterwards.

Alain Delon returns as Corey, a recently released criminal who becomes involved in the planning of a jewelry heist. He happens to cross paths with Vogel (Gian Maria Volonté), an escaped murderer. The two men team up and Vogel puts them in touch with an alcoholic ex-cop and sharp shooter, Jansen, who agrees to help them with the heist. Though the robbery goes off without a hitch, the police are hot on Vogel’s trail and the mob is after Corey.

By now, I have to admit, I’m tired of this being the sixth Melville film in a row where basically every major character dies at the end of the film, generally in a shoot out. Aside from the fatalist, if repetitive ending, Le cercle rouge is another of Melville’s classic films, mostly thanks to three great performances from Alain Delon, Italian actor Gian Maria Volonté (A Fistful of Dollars), and Yves Montand (Wages of Fear). Volonté and Delon in particular and wonderful together and their combined charisma drives the film forward and provides an emotional and moral center. Though both Corey and Vogel are criminals and murderers, they are loyal to one another and share the excitement of the heist and the drive for freedom.

Alain Delon returns in Melville’s final film, another tale of illicit heists and cops versus robbers. Delon plays Commissaire Coleman who is on the trail of three men that have robbed a local bank. One of them is hospitalized, but the three survivors use the loot to fund an even more extravagant heist. Coleman has his eye on one of his close friends, Simon (Richard Crenna), a club owner and the prime suspect. Coleman and Simon also share a mistress, the double crossing beauty Cathy (the sublime Catherine Deneuve).

Though this last film of Melville’s may not be his best, it is still well worth watching for fans of the director or the crime genre; I don’t think you can really enjoy the genre without a healthy appreciation for Melville’s influential work. Delon was excellent as a criminal in Le samouraï and Le cercle rouge and also shines as a slippery police commissioner, willing to bend laws and manipulate the women in his life. It also curiously presents on of Melville's most interesting female characters, a lovely transvestite working as a police informer who seems to be in love with Coleman. Un flic also marks somewhat of a change for Melville, as not everyone dies at the end of the film. It would be interesting to see what he would have come out with next, but he died of a heart attack when he was only 55.

Though I watched all of his feature films, Melville made a short at the beginning of career that I was unable to find. I think it’s a little strange that Vingt-quatre heures de la vie d’un clown (1946) aka Twenty-four Hours in the Life of a Clown hasn’t been included as an extra on one of Criterion’s many Melville releases, but hopefully that’s planned for the future, as several of their Melville releases have fallen out of print and either need to be reissued or released on Blu-ray

For more about Melville, there are a lot of great resources, including an enjoyable article from Senses of Cinema. Rui Nogueira’s important book Melville on Melville is sadly out of print, but will hopefully see the light of day again at some point. Your local library may have access to a copy. Check out Ginette Vincendeau’s Jean-Pierre Melville: An American in Paris, the only English language book on the director that is currently in print. Also look for the documentary Code Name Melville, available as an extra on the region 2 Blu-ray of Le samouraï.

I could not possibly say enough good things about this master of French cinema and innovator of the crime genre. His work comes highly recommended and, I think, it is best viewed as a group to observe the development of his many ongoing themes. For a visual example of the clear themes throughout Melville’s films, check out

this video essay, which shows common strains like characters smoking, domestic activities, men with hats, black and white tiled floors, characters looking into mirrors, etc.