John

Farrow, 1948

Starring:

Ray Milland, Maureen O’Sullivan, Elsa Lanchester, Charles Laughton

George

Stroud, the editor of Crimeways magazine,

is fed up with his controlling boss, Earl Janoth, and is ready for a

long-overdue vacation with his frustrated wife and young son. Unfortunately

Stroud is too good at his job, prompting Janoth to insist that he stay another

week in exchange for an all-expenses paid vacation, or be immediately fired.

Choosing the latter, Stroud misses the train to go on vacation with his wife

and instead gets drunk with Pauline, Janoth’s mistress and one of his only

secrets. Pauline convinces Stroud that they should get revenge against the

tyrant by publishing a tell-all book, but unfortunately Pauline is killed later

that night. Janoth panics and looks for a fall guy, all the while closing in on

Stroud, who is the only viable suspect.

Based

on Kenneth Fearing’s 1946 novel, The Big

Clock does not quite represent the best of film noir, but comes highly

recommended thanks to excellent performances from Ray Milland and Charles

Laughton. To be fair, I could watch Laughton (Witness for the Prosecution) in absolutely anything. He’s fantastic

as Janoth, the controlling, megalomaniacal, time-obsessed murderer. Bizarrely,

he has a Hitler-like mustache that he strokes throughout the film. Through

these little details, Laughton is able to add an air of sexual menace to a

character that is straight-laced, if not outright repressive, resulting in a

villain far more memorable than the film’s plot. Laughton’s real-life wife,

Elsa Lanchester (The Bride of

Frankenstein) nearly steals the film, as always, as an airheaded, yet sympathetic

artist who could make or break the whole affair for Stroud.

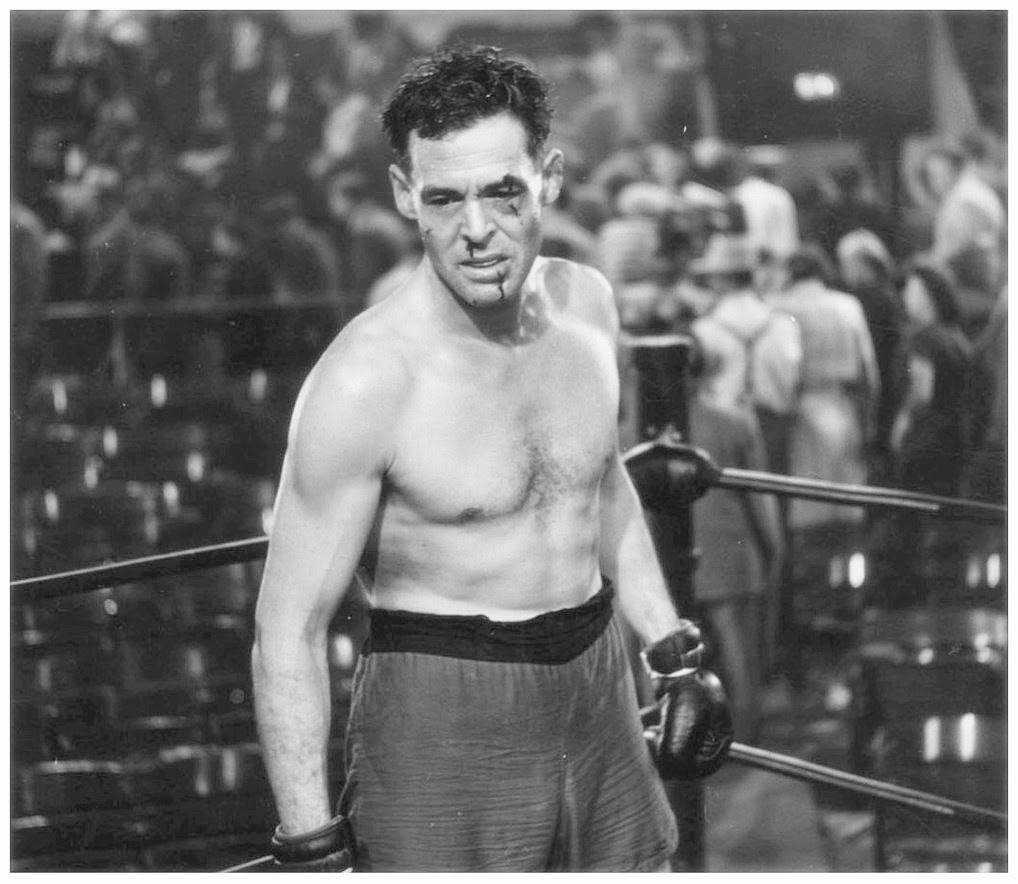

Ray

Milland (Dial M for Murder, The Lost

Weekend) is perfect as Stroud. A mixture of sympathetic and slimy, Stroud

is inherently flawed, not unlike other film noir protagonists. He purports to

hate his job, but refuses to quit and badly neglects his wife – for example,

they have been married five years and haven’t yet had a honeymoon. He should be

catching a train to meet her, but instead spends the night drinking with his

boss’s mistress. These two men seemingly at odds – Stroud and Janoth –

fascinatingly have a number of parallels. While Stroud complains that he is

overworked, he obviously strives in the fast-paced environment and it is his

innovations that have driven up the readership of Crimeways.

The

movie’s main flaw is that Stroud and Janoth are not pitted directly against

each other. Janoth is searching for a fall man, while Stroud is searching for

the real killer (primarily to exonerate himself), though they don’t realize one

another’s complicity in the crime until five minutes before the film ends. The

film also largely remains in lukewarm moral territory. Stroud neglects his wife

and outright ignores her to have drinks with another woman, but in the novel he

actually has an affair with Pauline. There is apparently allegedly a gay

subplot, which the Production Code would never have allowed to appear in a ‘40s

film. Both Stroud and Janoth’s characters, and the cold, modernist office

building filled with clocks – a reflection of Janoth himself – hints at deeper

resentments, aggressions, and plots. Janoth fires employees on a whim and

treats the rest appallingly. Those who do meet his approval, such as Stroud,

are manipulated, abused, and overworked.

This

was director John Farrow’s earlier films noir, though he would soon turn his

attention to the classic Night has a

Thousand Eyes, Alias Nick Beal again

with Milland, and Where Danger Lives

and His Kind of Woman with Robert

Mitchum. The Australian-born Farrow (father of actress Mia) began his career as

a writer, but pushed for directorial duties and event spent some time serving

in WWII with the Canadian Navy. His award-winning war film Wake Island, allowed him the luxury of choosing later projects. His

wife, Maureen O’Sullivan (Tarzan and the

Ape Man, The Thin Man), was persuaded to leave her temporary retirement to

take the role of Stroud’s downtrodden wife. Though she nearly leaves him, she

winds up helping to solve the mystery of Pauline’s killer. This resolves things

between them, though the film can’t help but end on an uneasy note, as Stroud’s

neglect of his wife was largely due to his personality.

There

are some nice supporting performances, including George Macready (Gilda) is fittingly slimy as Janoth’s

right hand man, while Rita Johnson (Here

Comes Mr. Jordan) adds some nice humor in her portrayal of the doomed Pauline.

A young Harry Morgan (High Noon, MASH),

Douglas Spencer (Double Indemnity), and

Lloyd Corrigan (It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad

World) round out the cast, while John Seitz (Double Indemnity) provides some lovely cinematography – much of

which is clock-themed – and Victor Young (from The Uninvited) delivers an imaginative, somewhat whimsical score,

fortunately one that is less clock-themed.

Available

on DVD, The Big Clock comes

recommended, particularly for fans of Ray Milland and Charles Laughton. And if –

for shame – you don’t who Laughton is, then you should definitely give The Big Clock a try. It’s a pleasing

film noir that somewhat breaks out of the predictable mold and offers up enough

humor and suspense to keep this from being a nihilistic doom-fest (though I

personally love those too). Fans of Hitchcock will probably also find this

worth watching.